No. 1

Part 2 of an excerpt from my memoirs-in-progress. Part 1 is the previous post.

BY THE END OF MAY I had found three designers and tried to work out the copy flow with the editors. We thought we all understood what to do, but each had assumptions based on different experiences. Fleming and Sherrill came from big publications and were used to teams of people editing copy, setting type, and making up pages. I came from places where we improvised and shared the work equally in the hope that we would go to press on time.

While New York magazine had defined itself as a survival guide to the city, LA was to be more like the Village Voice, the weekly tabloid started in 1955 that defined the “alternative newspaper” genre. There was to be actual writing—on interesting people, the culture of the city, the popular culture it helps produce. Politics would be analyzed but not covered like a newsmagazine.

We started worked on the first issue with increasing fury. One problem was the cover story, a biting piece about disco, class, and drugs, like features in Vanity Fair ten years later: “The Paradise Ballroom,” by John Fleischman (another starting reporters who went on to a successful career as a writer). The photos available were dark club shots of people who were not recognizable, at least not to me. I wanted to convey the slickness of the LA club scene for the cover, and engaged Brian Davis, a young airbrush artist (later quite successful).

But the editors thought the result was tawdry. They opted for a paparazzi-style photo of the club owners that Davis had worked from. (Photo credit: “Eduardo.”) A big caption under the photo started: “The Other Side of Paradise.” Along the top of the page (not obviously connected, as I can see now) was a banner set in Egiziano, “Cosmic Outlaw.” With the picture running three-over-four columns wide, I had made a tabloid-looking front page. Turning up the sensationalism one more notch was an image of a big guy without a shirt and the heading, BLACK JESUS.

After the issue came out, the phones rang off their hooks, and we all jumped to take calls. I answered one, “LA,” and an older female voice said, “Is this Cosmic Outlaws LA?”

Learning the difference between design and art directing

The cover illustration ran inside, but it I didn’t blame the editors for rejecting it as a cover. As a fledgling art director, I was clueless on how to achieve the Hollywood sheen of record album art, but I thought we should get the style into the paper. I assigned several pieces to Davis and Blue (who later teamed up), as well as Blue’s partner Joan Nielsen, who accepted the low fees that were in my budget. But I couldn’t make it work, and I moved on to more familiar territory. Peter Green, a talented caricaturist, did several covers for LA, as well as inside art—not all of them “cartoons.” There was a cover showing the Los Angeles Times Sunday magazine, West, sinking in the ocean. Its famous art director Mike Salisbury, a master of the slick 70s style, suggested the idea.

For a profile of Francis Ford Coppola by Stephen Farber (who went on to a long career writing about the movies), Green put a charcoal drawing of the director’s head on a still from The Godfather, the scene where the padrino’s ring is being kissed. It worked, maybe better than an airbrushed retouching job.

Green would try anything. I had tried a clip-art free-press engraving on the top of the masthead, and one of the editors suggested we do our own. So, Green did a line drawing in ink of an eagle gripping a banner with a legend in Latin, “Angeli Ama aut Relinque.” Los Angeles, Love It or Leave It.

The greater part of the visual content of LA was the photography. The circle of photographers I met at Cal Arts netted our staff photographer, David Strick, who was willing to shoot anything from a quick head shot, to sports, to a whole photo story. An LA native, he was the great nephew of Gale Sondergaard who won the first Oscar for supporting actress. His father, Joseph Strick, directed Ulysses, and his mother was a successful Hollywood publicist. Strick, like many good photographers was quiet and modest, and he hadn’t talked about his Hollywood family until the day I was saw on a contact sheet that he had finished the roll with random shots from home. He lived with his parents, and having just moved out of my parents’ house, I was curious to see what it was like. There was a bookcase filled with books and memorabilia, and there on one shelf was an Oscar. I asked, “Is that an Oscar?!”

“Yes,” he said quietly. “My father got the Academy Award last year for the best short documentary.” As a still photographer, Strick was learning fast, and he had an eye for people. His subjects responded.

Peter Karnig contributed highlights from a big suburban project, shot in what he called the “dirtball town” of Newhall, the original rural outpost in the Antelope Valley before Valencia was developed. (This area, including Valencia, the development were Cal Arts was built, is now incorporated in the city Santa Clarita and sprawls along I-5, up and over eastern side of the valley.) His pictures, with captions by John Kaye, showed an America that few of the folks in West LA knew existed. In the context of LA, that essay foretold a divide in the surging metro area (and in the whole country) between the wealthy elite and the working Americans. The hard light and the detail of each portrait makes these pictures look fresh 50 years later.

Jed Wilcox was another photographer from Cal Arts. We gave him some assignments and picked up a number of his personal shots, including my favorite, with his friend Lynn “Napoleon” Lascaro jumping into a wave in Santa Monica.

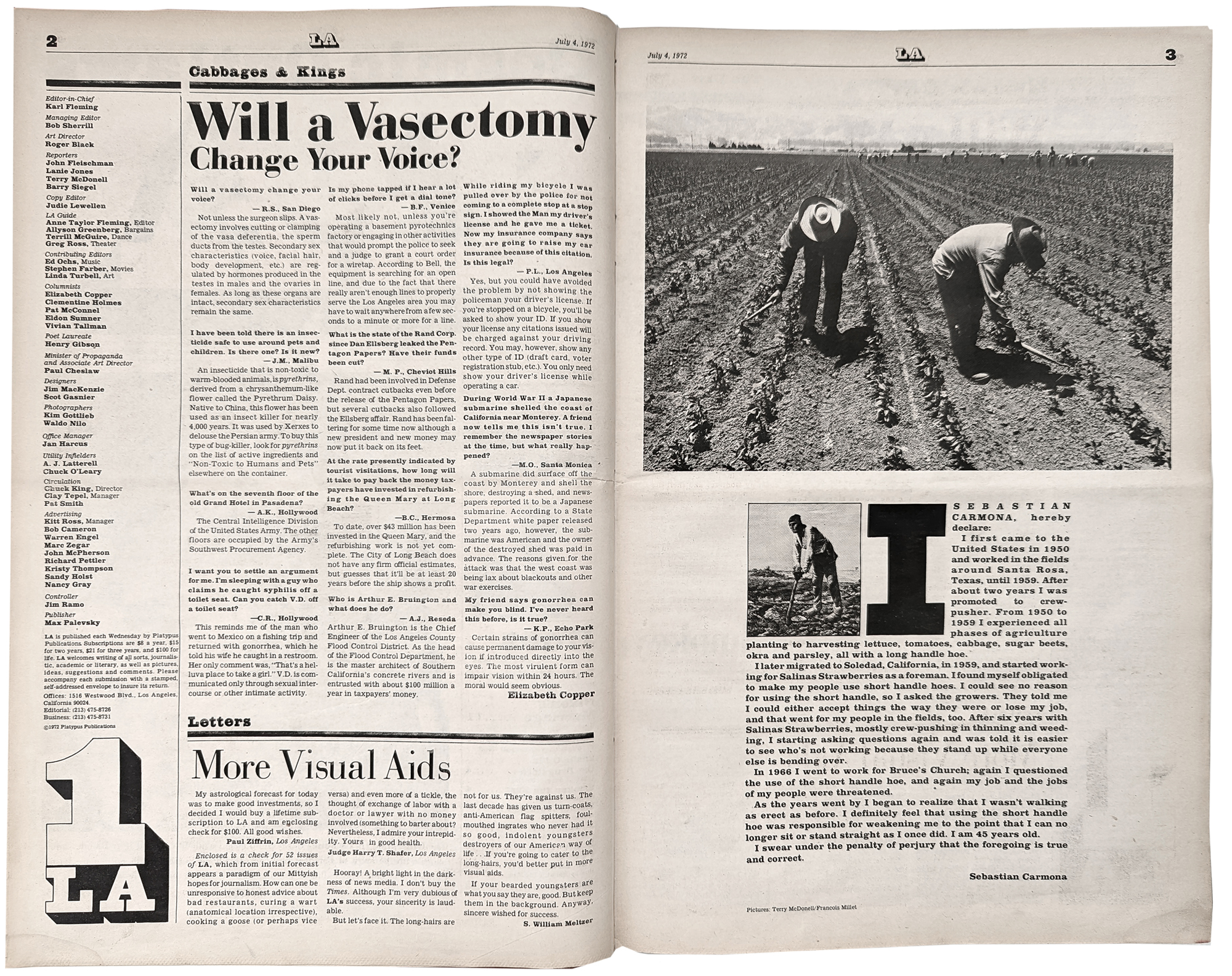

Several staffers took pictures, including Barry Siegel and Karl Fleming, himself. The best was Terry McDonell, who had worked as a AP photographer before turning to reporting. For a Christopher Isherwood profile by Anne Taylor Fleming, he got three portraits, plus a cover. Harder-edged was a four-page photo essay on the fundamentalist sect of Tony and Susan Alamo, accompanying a feature by Tom Moran. McDonell took the front-page picture of a soulful young man looking straight into the camera, holding a plate with his dinner. “Thank You, Jesus” was the headline. (Later, McDonell’s experience as a photojournalist helped him push the visual side of the magazines he edited.)

Most of my attention at LA was directed at the typography, the laying it all out. Just getting a 32- or 40-page issue set in long columns on shiny photo paper, repro proof, and then pasted up on illustration boards for the printer amounted to a volume of work I wasn’t quite ready for. LA’s Mergenthaler VIP typesetting machine was on back order, and we had to send the type out, which added hours to the turnaround. For the body type, I had to settle for Corona instead of Ionic No. 5.

The first issue was late to the printer, which put stress on our distribution, which was being managed in a rough-and-ready way by Chuck King (aka Charles Kane), largely through “honor boxes,” the coin-operated vending machines placed next to stores. King was not the kind of guy you would argue with.

The editors blamed the art department, but I already knew that most writers have no idea how a newspaper is produced. Talking to Judie Lewellen, the copy chief, I concluded that copy flow was not going to be managed by, say, the managing editor. We needed to bring in a production manager to police the deadlines. I thought of a persistent job applicant named Michael Parrish, who seemed to have an instinctive understanding of newsrooms, and a willingness to take any position right then. A graduate of Reed, wearing the black leather jacket I associated with Reed alumni, Parrish would have a better chance of corralling the editors than I would, as an art person, or than a neutral business-side hire. I asked him if he would start as production manager, and he said, yes. After a No. 1 issue postmortem meeting, I asked Fleming to meet Parrish, and he hired him.

Soon he had copy flowing on schedule, and we could all concentrate on the content. Parrish became an accepted part of the editorial team, and Fleming listened to his ideas for stories. (He later went on to be editor of the Los Angeles Free Press, the “Freep,” which evolved from an underground to something more like LA, an alternative weekly. In San Francisco, he became editor of Coppola’s City newspaper, and then, in 1985, the first editor of the Los Angeles Times Magazine, taking the Sunday slot that had been vacant since the scuttling of West .)

While struggling with the art, I leaned hard on the type. There was a quick evolution of the format in an effort to make the layouts more dynamic. I wanted to get people to turn pages. Longer stories started spilling over right hand pages onto the following left hand page without a “continued” line, which magazines didn’t need.

Column headings were reinvented after ten issues, while departments kept their Egiziano kickers above a custom rule that stretched the width of the column. I snaked items in the columns and tried to interject unrelated pieces onto a page, to break of the linear features.

I did know from the beginning, from my own habit, that nobody reads everything in a publication. But I had not yet grasped the fact that a reader always looks at pictures first, and then read the captions. Making a rule that there is a caption under every picture gives quick summaries or hints of content, and lends a little satisfaction. A reader could feel that the issue was read even if they skipped many stories. This fact was confirmed decades later by the eye-tracking studies publishers did.

Sherill would write great subheads (chapter titles) to break up text. They’re also called “breakers.” They can give the reader a sense of a story and its momentum. I learned to call him when I needed some clever text. Laying out the first classified ads (two lines free, no sex), I asked him for a tagline. “What?” he said. “Like under the headlines in Esquire, something ironic,” I said. He frowned, grabbed a sheet of foolscap (newsprint from the end of a roll at the printer) and quickly typed: “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride. Saddle up!”

I used it, of course.

The big agate session was the “LA Guide,” which ran for six pages, covering arts, clubs, movies, TV, and sports. There were listings for places to get emotional help, to take your kids, adopt pet, attend a class—and a few random interesting events. It was edited the old fashioned way, by rewriting every entry. The editor was Fleming’s wife, Anne Taylor Fleming, an LA native. (Ms. Fleming went on to publish both non-fiction and fiction books, with a feminist angle. She wrote a column for The New York Times Magazine, and was a regular commentator on CBS Radio, and then the “NPR News Hour.”)

Living in LA

Los Angeles was easy to get used to. A change for me from the older cities (New York, Chicago, or Washington), it shared the new, chaotic, automobile-centered sprawl of Houston. Unlike Houston, which my friend Tom Curry described as “nice and flat,” it was a geographical delight. LA had the ocean to the west, and the mountains on the east, when you could see them. Supposedly, air pollution was declining, but the San Gabriel Mountains were visible behind the downtown buildings only on the day after a winter storm. Pasadena, a garden for the rich in the 1920s, had started to decline in the 60s because of the smog, and I avoided it, as I did the entire San Fernando Valley.

[To be continued in Part 3]

The inside spreads of LA No. 1